When one thinks of an admiral, they likely think of someone who has spent all his life near or on the sea. Chester W. Nimitz took an unlikely journey, coming from the middle of the Texas Hill Country to commanding the U.S. Pacific Fleet during World War II.

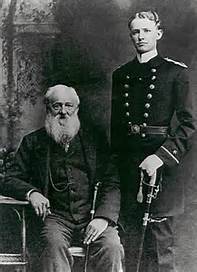

Nimitz grew up hearing stories of the sea from his grandfather, Charles H. Nimitz. Charles was a German merchant marine captain who immigrated to Texas and built a hotel in Fredricksburg. He also served as a father figure to Chester, whose own father Chester H. Nimitz died before young Chester was born in 1885.

Chester Nimitz originally wanted to attend the U.S. Military Academy after he met a couple of recently graduated second lieutenants. He contacted his local congressman, who said the West Point slots had been filled, though he had an appointment for the U.S. Naval Academy. Nimitz studied and passed the competitive exams, and went to Annapolis.

Captain Charles H. Nimitz left, with his grandson Chester W. Nimitz (photo credit: pacificwarmuseum.org)

Nimitz became a career Navy man. He developed an expertise in submarines and diesel engines. Yet he was better known for his people skills, and eventually became chief of the Bureau of Navigation (the precursor to today’s Bureau of Personnel). He was serving in this role when Japan attacked U.S. forces on December 7, 1941, at Pearl Harbor. Following the attack, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ordered Nimitz to take over the Pacific Fleet.

Upon taking command, Nimitz made clear that he wanted all his predecessor’s staff to remain at their posts. There would be no courts-martial, demotions, or transfers. In this way Nimitz helped to rebuild the morale of the staff, which understandably was shaken after the attack.

Nimitz said that winning the war was a matter of arithmetic: subtraction for the Japanese, addition for the Americans. To help identify and resolve issues in day-to-day operations, he posted a sign over his desk with questions that his staff would be expected to consider when making plans:

- Is the proposed operation likely to succeed?

- What might be the consequences of failure?

- Is it in the realm of practicability of material and supplies?

For all of his contributions, however, Nimitz never wrote a memoir or autobiography. This reticence was due in part to an episode Nimitz observed as a young officer, in which a controversy arose because certain officers argued over their role during a battle in the Spanish-American War. Nimitz didn’t want to see a repeat because of something he said or did.

Nimitz was the third of four admirals to receive five-star rank. (William D. Leahy and Ernest J. King were the first two admirals so honored. William “Bull” Halsey was the last admiral to receive a fifth star.)

After the war, Nimitz served as Chief of Naval Operations and later as a United Nations goodwill ambassador. He and his wife, Catherine, settled in Berkeley, California, where they stayed in touch with family, friends, and welcomed guests. One guest was Mitsuo Fuchida, the pilot who led the first attack wave at Pearl Harbor and who went on to become a Christian evangelist after the war.

Fuchida’s inscription in the Nimitz guestbook was, “No more Pearl Harbors.”

Sculptor Ric Caswell created this statue of Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, which stands outside the Nimitz Hotel in Fredricksburg (photo credit: caswellsculptures.com)

Chester Nimitz died on February 20, 1966, and was buried at the Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno, California. Among other honors, the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz (launched 1972) and the Nimitz Library at the U.S. Naval Academy (1973) were named for the admiral.