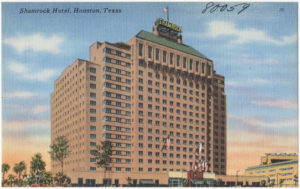

A Shamrock Hotel postcard (Creative Commons license attribution: image courtesy Boston Public Library)

A few years ago, I attended a Houston history panel discussion in which the topic was the fate of the Astrodome. It remains a timely topic because of the Astrodome’s historical significance. It is also timely because the Astrodome represented qualities that many associate with Houston and Texas itself—bold, elaborate, larger than life, and unique.

Like the Astrodome, the Shamrock Hilton hotel met all these qualities.

The hotel was built at the intersection of South Main and West Holcombe, near the Texas Medical Center. It’s hard to imagine now, because Houston is so spread out, but when the hotel opened it drew attention in part because it was more than a mile from downtown.

It’s been suggested that the man responsible for building the hotel chose the location after a falling-out with the downtown crowd. Others suggested that he saw that the city was growing towards the south, towards the Medical Center and Rice Institute.

Glenn McCarthy, an oil wildcatter originally from Beaumont, envisioned and built the hotel, originally known as the Shamrock Hotel in deference to his Irish heritage. (An oil wildcatter is an oil man who drills in areas not known for their oil fields. These wells are called wildcat wells, thus the nickname. McCarthy was pretty good at the oil business, or at least got his share of notoriety for it. He was known as the “King of the Wildcatters.”)

So McCarthy led efforts to build the hotel. It opened on St. Patrick’s Day, 1949, and received national media coverage. In a 2009 Houston History magazine article, writer Diana Sanders described the hotel:

“The eighteen-story building boasted a 5,000-square-foot lobby adorned with Bolivian mahogany paneling and Art Deco trim. The color scheme throughout the hotel consisted of sixty-three shades of green, a tribute to McCarthy’s Irish lineage. The hotel’s 1,100 rooms had air conditioning, and each had a television, push-button radios and abstract art works. One third of the rooms had kitchenettes. These were extraordinary amenities for 1949. Surrounding the Shamrock was an elaborately landscaped garden and terrace. The hotel’s pool measured 165 by 142 feet, with a three-story diving platform accessible by an open spiral staircase.”

The hotel drew celebrities, heads of state, and other VIPs of the day. Yet not everyone was so positive about the hotel. In a 1989 KPRC-TV documentary about Houston, journalist Ron Stone shared a story about the architect Frank Lloyd Wright being invited into the hotel to have a drink at the bar. Wright was supposed to have said, “Well, I don’t know. I’ve never been inside a jukebox before.”

A 1950 photo of a sales convention at the Shamrock Hotel. (Creative Commons license attribution: photo courtesy Nathan Hughes Hamilton)

In the years following World War II, McCarthy decided to diversify his investments. The hotel was his most famous. But he overextended himself, and eventually sold the hotel to the Hilton Corporation, which changed the name to the more familiar Shamrock Hilton hotel.

The hotel struggled in part because as Houston grew and freeways were built to address the development, no freeways were built near the Shamrock Hilton. Other, less ostentatious hotels were being built closer to the freeways and were more convenient for travelers.

When the energy industry struggled in the 1980s, the Hilton Corporation donated the hotel to the Texas Medical Center, which concluded that the hotel was no longer economically feasible. Over protests of some, including McCarthy himself, the hotel was demolished in 1987.

McCarthy died in December, 1988. He was 81. Some have suggested that his passing was in part due to a broken heart over the demise of the hotel he envisioned and built.

Today, the Texas A&M University Health Science Center, a parking lot, and a small park owned by the university occupy the site. No historical marker commemorating the Shamrock Hilton exists there.

At the panel discussion I attended, one panelist suggested that the Shamrock Hilton’s demolition caused Houstonians to change their minds about historic preservation. That people were discussing ways to save the Astrodome by repurposing it, he said, would never have happened in the days before the demise of the Shamrock Hilton.